Tamworth Pig Stories Read online

FOR EVA

WITH LOVE AND THANKS

Ah! Tamworth Pig is a very fine pig

The best you’ll ever see,

His ears stand up, his snout is long,

His score is twenty-three.

He’s wise and good and big and bold,

And clever as can be,

A faithful friend to young and old

The Pig of Pigs is he.

BY COURTESY OF MR RAB

‘… Pigs of the Tamworth breed … are

creatures of enchantment …

ANONYMOUS PIG-FANCIER

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

The Prime of Tamworth Pig

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Tamworth Pig Saves the Trees

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

About the Author

About Faber

Faber Children’s Classics

Copyright

THE PRIME OF TAMWORTH PIG

CHAPTER ONE

Thomas sat on top of a grassy hill on a warm, windy, April afternoon.

‘Yoicks,’ he shouted into the breeze.

He felt wonderful, having just recovered from mumps, measles, chicken-pox, German measles, scarlatina and whooping cough. But, at last, he was better; there didn’t appear to be much left to catch and the doctor had said he needn’t go back to school till September.

‘Just let him run wild,’ were his words.

‘If he’s at home running wild, then I shall go to school to keep out of his way,’ Daddy had replied.

Thomas bellowed to the fields and hedges all around:

‘No more school, mouldy old school,

No more school and sorrow,

Lots and lots of holidays

Before there comes tomorrow.’

He rolled over and over down the hill at the sheer bliss of his thought, followed closely by Hedgecock and Mr Rab who were arguing as usual.

‘You’re not in the least like a real rabbit. Don’t make me laugh.’

‘Yes, I am. I am. Say I am, please. Just a bit like one.’

Hedgecock snorted loudly.

‘I never saw a real rabbit with a red and white striped waistcoat, a green bow tie, and skinny, pink, furry legs. You’re enough to make a cat laugh – to say nothing of a real rabbit.’

‘Well, what about you? What are you, then? A hedgecock with feathery prickles. You can’t fly and you can’t prickle.’

‘But I’ll tell you what I can do. I can bash you, Stripey.’

He proceeded to do so. Mr Rab roared with pain. He was no match for Hedgecock.

‘Stop that,’ Thomas commanded. ‘I’ll do the bashing round here. Come on. What shall we do?’

‘The stream,’ Hedgecock said. ‘We’ll go to the stream.’

‘Yes, to the stream; let’s go.’

They ran over the grass, Mr Rab trying to dodge the daisies; he was soft-hearted over flowers, over everything in fact, except Hedgecock, and he hated treading on daisies.

Suddenly they were there. Banks, two or three feet high, covered with mossy rocks just right for sitting on, bordered the clear water. The trio sniffed eagerly. It smelt good, as ever. Perhaps it was the bracken, or the wild thyme, or perhaps it was just the stream itself that gurgled over the brown stones on the sandy bed. The path ran into a curving bay and stepping-stones crossed to the other side. Farther down there was a stretch of grassy turf covered with molehills and mole-holes. Thomas walked into the water, still with his shoes and socks on, and tried to catch minnows shooting this way and that. Then he sat down on a stone and contemplated his feet (over which the stream rippled making very interesting patterns) for some time.

‘I know, let’s make a dam,’ he said at last.

They chose a spot where the stream narrowed between high banks. Hedgecock worked steadily, counting the large stones (four-five-six-seven-eight-nine-ten-eleven) as he carried them to Thomas, who rammed them into position against the log they’d pushed across the stream. Mr Rab was ordered to plaster mud and sand into the gaps. He whimpered to himself, for the water was cold and his paws hurt. Water still rushed through the spaces between the stones but its colour was turning to a reddish-brown, and gradually it slowed down and began to spread out on the flat, grassy ground above the dam.

Mr Rab sat on a rock, tucking his wet paws under his waistcoat, and stuck his thin legs into the sunwarmed grass. The other two ignored him, as they continued to stuff pebbles, mud and grass into every crack. Mr Rab began to recite in his special voice that he kept for poetry, which was a kind of high, wobbly moan.

‘There s a stream on a grassy common

Runs very swift and clear …’

‘You can cut that lot out,’ Hedgecock shouted. ‘I hate your rotten poetry. If you’ve enough energy to say that old rubbish, then you’d better come and help.’

But Mr Rab wasn’t listening. ‘Look! Look!’ he shrieked.

The others turned round to see why he was dancing about and pointing a quivering paw. Upstream of the dam, the water was now several feet wide and all the moleholes had disappeared beneath it. There on the grass, shaking their fists, were dozens of angry moles.

‘You horrible beasts,’ the Chief Mole shouted, leaping from one damp foot to the other. ‘You’ve wrecked our homes. You nearly drowned us all.’

‘We didn’t mean …’ Thomas began.

‘Yes you did. You did it on purpose. I know you. We all know you. Terrible Thomas, that’s who you are; you – you – you—’

The mole spluttered with rage and wetness.

Mr Rab was dashing the tears from his eyes and Hedgecock was trying to hide in the bracken.

‘I’m sorry,’ Thomas muttered. ‘We’ll undam: I mean, we’ll knock it down. Hedgecock, stop creeping away. Come and help.’

With one accord, they and the moles all began to demolish the dam. It came down much faster than it went up, Hedgecock noted bitterly. Soon the stream was flowing as noisily and happily as before.

‘It will be all right now,’ the Chief Mole said. ‘We shall dry out in the sun. I don’t think you meant it after all.’

‘No, we didn’t.’

‘Next time, build farther up there and then it won’t affect us.’

‘But will there be a next time?’ Mr Rab moaned. ‘Look at us.’

Silently they inspected one another: wet, scratched, plastered with mud. Thomas had torn his trousers and lost his shoes and socks.

‘Come on, there’s going to be trouble,’ he said.

At that moment two figures leapt from the bank and pushed Thomas flat into the stream. Even as his head was held down into the cold water, while their feet kicked him, Thomas knew who they were – Christopher Robin Baggs (most unsuitably named), a spotty boy with stick-out teeth, and his rough, tough friend, Lurcher Dench, both enemies of Thomas. He had fought many battles with them, but he had thought they were at school today, and so he had not been on the look-out. He squirmed and struggled and kicked under their combined wei

ght. Then one of them stood on his legs. It hurt.

‘Let’s drown old Twopenny Tom,’ they were yelling. ‘Down with Measle Bug.’

Somehow he got his face out of the water. Hedgecock was snapping and biting but Mr Rab had disappeared. The rage inside Thomas was bubbling like a boiling cauldron. Fancy letting himself be caught like this and without shoes. He couldn’t have been more defenceless. The terrible thought shot through his head that perhaps they really did intend to drown him, as Lurcher once more ground his face down into the sand and water. There was a roaring in Thomas’s ears and stars shot across the blankness that was enveloping him. The roaring crescendoed into a mighty sound that was somehow not in his head and as if by magic, the weight lifted off him, the kicks and blows and the pain ceased, and he stood up shakily to see the backs of his attackers running away as if pursued by demons. Mr Rab’s soft paws were stroking his sore legs as Thomas stumbled forward to his rescuer.

There on the bank stood a huge, golden pig, a giant of a pig, the colour of beech leaves in autumn, with upstanding, furry ears and a long snout.

‘Tamworth!’ Thomas gasped, spitting out water, sand and the odd tooth. ‘Oh! Tamworth, I am pleased to see you. How did you know?’

‘Mr Rab fetched me – ran like the wind, he did. I wasn’t far away. Funny the way those two objectionable boys fled when they saw me. I can’t think why. I’m a most amiable animal and I don’t believe in violence.’

‘I ache all over,’ Thomas said, investigating his bruises.

‘Up on my back, all of you. Home we must go. Your mother will undoubtedly have a few words to say. Humph! Don’t wet all my bristles.’

‘Giddy-up, Tamworth,’ Thomas said, holding tight to the golden back.

Thomas’s mother did, in fact, have a great many things to say when he arrived home; she went on and on for a considerable time. Later, he lay very carefully in bed because of his many bruises, and buried his face in Num. To everyone else, Num was just a piece of shabby, grey blanket but to Thomas, Num was warmth and softness and comfort in times of sorrow. Wriggling gingerly into the welcoming folds, he said to Mr Rab:

‘Sing a bedtime song.’

‘Not that old muck,’ Hedgecock growled.

‘Go and count your squares if you don’t want to hear it.’

Hedgecock retired muttering to the blanket of knitted squares at the foot of the bed. There were eight one way and ten the other, all in different colours. Hedgecock loved to count them in tens, or twos, or ones.

Mr Rab sang reedily. This was a special poem and he’d made up a tune to it, of which he was very proud.

‘Mr Rab has gone to sleep

Tucked in his tiny bed

He has curled up his furry paws

And laid down his sleepy head.’

‘Seventy-eight, seventy-nine, eighty,’ droned Hedgecock. Then there was a loud snore as he, like the others, fell asleep.

CHAPTER TWO

Blossom, Thomas’s sister, had a day’s holiday from school and so got up very early, full of cheer. She laid the breakfast, took tea to Mummy and Daddy and then woke up Thomas to play a game of Monopoly. Thomas liked games but hated to lose and he hated paying out any money so from time to time he would rush from the room roaring and stamping with rage. Then, having simmered down, he would come back.

Blossom remained quite unperturbed by all this, merely continuing with her book till his return. She was a round, brown-eyed girl, rather like an otter, with an amiable disposition and a kind heart. Like Mr Rab she loved poetry and hated sums. She couldn’t understand, at all, Thomas’s wish to win everything. In a good game winning didn’t matter. She was as warm and comfortable as a bed at the end of a tiring day and sometimes silly, with a great and glorious silliness, just to show she wasn’t too saintly after all.

The game came to an end with Thomas hurling the board across the room as he was obviously going to lose. Money, dice, tokens, houses, hotels flew through the air.

‘I hate that stupid game,’ he shouted.

‘Only because you’re losing,’ Blossom said calmly, picking up the debris.

They then went down to breakfast, and afterwards set off for Baggs’s orchard to see Tamworth Pig, for he always welcomed visitors and conversation. Tamworth belonged to Farmer Baggs, whom he liked, but was looked after by Mrs Baggs – a mean woman – whom he hated. Christopher Robin Baggs we have already encountered. His warfare with Tamworth and Thomas had gone on for a long time, dating probably from the time when he’d tried to set fire to Tamworth’s straw to see how quickly the pig could move. Actually it was Christopher who did the moving, pursued by an inflammatory Tamworth.

When Blossom and Thomas arrived, Tamworth was deep in conversation with Joe the Shire Horse.

‘The price of pig food has gone up again, Joe. It’s ridiculous. Mrs Baggs hardly gives me a decent meal as it is, just a lot of old scraps, scarcely sufficient to maintain a budgerigar in good health. Now I suppose she’ll give me even less. Hello, Blossom. Hello, Thomas. Have you heard? The price of pig food is up, and eggs and butter are to cost more. And this isn’t necessary. The economic situation of this country is due entirely to inefficiency. Now, if I were Prime Minister, everything would soon be different.’

‘Why? What would you do then?’ Joe asked slowly.

New ideas were always difficult for Joe.

‘Well, I’d put the most important thing first.’

‘And what’s that?’

‘Why, food, of course,’ Tamworth said. ‘We can’t live without food. We can’t work without food.

Food keeps us going and I also think it’s one of the best things in life. The very best possibly.’

‘I believe you’re right,’ Blossom agreed.

She felt in her anorak pocket for a toffee that she seemed to remember leaving there, for she dearly loved to eat.

‘I’ve brought some apples for you.’

Thomas emptied the contents of his brown paper bag on the floor.

‘They’re a bit wormy, but all right.’

Tamworth gobbled them down and then continued speaking.

‘Well, then, since food is the most important thing in life we should gear our whole existence to its production. Think, for example, of all the waste ground in this country. It should all be used to grow more food, potatoes, mushrooms, peas, lettuce, tomatoes, onions and lovely cabbage. Children should be taught to grow and make as much food as possible. Everyone could make more sweets, toffees and chocolates, and cakes, and biscuits, and buns and bread, and there would be lots and lots for everyone. We could even send tons of food abroad to feed the starving people.’

‘What about the ’orses?’ Joe asked. ‘What about my ’ay?

Joe had a one-track mind which seldom moved far from the thought of hay.

‘Tons of hay go to waste every year on the grass verges by the sides of the roads. It should all be used. Extra food, better food could then be given to all the cows and hens, who would give more butter, cheese and eggs. More of everything for everybody except MEAT. Meat,’ Tamworth repeated firmly, ‘is bad for everyone.’

Tamworth’s feelings about meat were very strong.

‘Yes, that should be our country’s motto, MAKE MORE FOOD. And if I ever become Prime Minister, it will be the first point on my programme.’

‘GROW MORE GRUB would sound better,’ Thomas suggested.

A voice was heard calling for Joe and he lumbered away, brooding on the prospect of unlimited hay.

‘Tamworth,’ Blossom said slowly, ‘you’re known as a very wise pig. Tell me, how can we make some money?’

‘Why do you ask?’

‘Well, you know, I think we must be very poor because every time I want something, Mummy says, “Do you think I’m made of money?” and Daddy’s always grumbling about bills and income tax. And then Gwendolyn Twitchie has twice as much pocket money as I do.’

‘And you have twice as much as me,’ Thomas grumbled. ‘It’s not fai

r.’

‘I’m older than you.’

‘Yes, but you’re much more stupid, so I ought to get as much as you.’

‘Stop arguing,’ Tamworth commanded. ‘I shall have to give this some thought. Have you got another apple?’

‘No, you’ve eaten them all.’

‘Well, it’s time for my morning nap now. Call again soon and I’ll let you know if I’ve thought of anything. Oh, and can you draw lots of posters with “Make More Food” on them, and I’ll get them distributed. I feel I must start a campaign, in view of this rise in the price of pig food.’

He turned round twice in his comfortable quarters, pushed his straw into a heap and flopped down.

‘Scratch my back, please, Thomas. The stick’s over there.’

Thomas scratched the bristly, golden back and Tamworth closed his eyes in contentment. Soon a gentle, whiffling noise filled the air.

‘He’s asleep,’ Blossom whispered.

Tamworth opened one small, bright eye.

‘I’m not. I’m thinking, Good-bye.’

They wandered slowly home. The sun was shining. It was a beautiful day.

‘Let’s play in the tree-house with Hedgecock and Mr Rab,’ Thomas said.

‘All right.’

And they raced back to the house singing ‘Green grow the rushes-oh!’

After that the day suddenly went wrong for Thomas, for who should be awaiting Blossom but Gwendolyn Twitchie. Instantly Blossom turned into a different creature.

‘Let’s be princesses,’ they squawked and ran giggling into the bedroom.

Thomas banged on the door and shouted, ‘Let me in, you stupid fools!’ but they only tittered and piled things against the door so that he couldn’t shift it at all. He fetched his hammer in order to batter it down, but Daddy appeared, roaring like a lion. He sent Thomas into the garden, where he wandered dismally into the tree-house with Mr Rab and Hedgecock. They couldn’t seem to start off a good game, but sat arguing feebly, making patterns in the dust with their shoes.

The Puffin Book of Ghosts and Ghouls

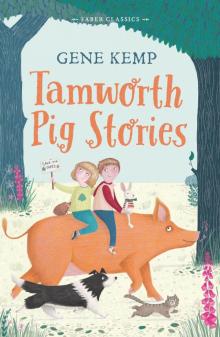

The Puffin Book of Ghosts and Ghouls Tamworth Pig Stories

Tamworth Pig Stories Goosey Farm

Goosey Farm